- Home

- Anya Yurchyshyn

My Dead Parents Page 3

My Dead Parents Read online

Page 3

This mistake was easy to make because my mother dressed me in gender-neutral clothes. Denim overalls and plain turtlenecks, sneakers without any pink on them. She dressed my sister the same, but her hair marked her as a girl. I was jealous that my friends got to wear skirts and dresses. When I asked my mother why I couldn’t, she told me that she wanted me to be able to play like a boy, to hang on the jungle gym without having to worry about showing my underwear. I wanted to play like a boy, but I also wanted people to see my underwear.

I was tiny, always the smallest in my class, and though I’d been a chubby baby, I quickly developed my mother’s slight frame. Because my ribs stuck out, my sister called me “the Ethiopian,” telling me that I looked like the starving children we saw on the news and who our parents invoked when we didn’t finish our food. Doctors were concerned by my size and inability to gain weight, and X-rays of my hands or feet were a part of my annual checkups. I loved getting X-rays, wearing the heavy lead shirt, being in the room alone, and getting to see my bones. But in the films my doctors saw problems. They were worried because my hands were the size of a five-year-old’s, not an eight-year-old’s. Their assessments supported my father’s: Something was wrong with me. I was supposed to be different, better than I was.

When I started school, my deficiencies became even more conspicuous. I was a slow reader, had terrible handwriting and spelling, didn’t get math, and couldn’t sit still. I started working with a specialist, but my work didn’t improve. My problems in school sparked a new anger in my father. It was sharp and obsessive, wild and guaranteed.

When he was away, I did my homework on the living-room floor or on my bed. My mother would help me when I got confused and sometimes looked over my work to make sure it had been done, but she seemed happy to cede responsibility for my education to the school. When he was in Boston, my father was in charge of my homework, and doing it was a battle I came to dread. When he got home from work and was ready for me, he’d call my name and I’d limp toward him, queasy with despair.

He made me sit at the long wooden table my parents had bought when they’d lived in London. It was the same place where he worked on evenings and weekends. Under his tight gaze, I’d spread out my sheets of math problems and handwriting exercises, a passage to read and respond to. I started with math. I’d clutch a yellow pencil and read the instructions aloud. My father was impatient before I even began, correcting my pronunciation and sighing. “Come on, you know that word.”

I talked my way through each problem so he could understand my approach, and with every correction, I became more hesitant. I pulled my worksheet toward my chest. As his patience drained, his breath became short and fast. Sensing his annoyance, I started to rush, to get somewhere near an answer and jot down a number.

“Anya!” He grabbed the pencil and slammed it down. “That answer is wrong, and you know it. Do it again!”

I picked up the pencil, but I was so nervous that I blurted out another wrong answer.

He sighed and walked away, then returned. “Do the work.”

What did it mean to “do the work”? You either knew the answer or you didn’t. I guessed again.

“What are you, stupid?” he hissed.

Stupid. The word made my entire body ache. I cringed as my eyes filled with tears. I kept my head still, trying not to blink, and hoped that they wouldn’t escape.

“Are you?”

“No,” I bleated, and my tears, so many more than I’d thought could be in my head, leaked out.

“Stop,” he yelled. “Don’t be a crybaby.”

I wanted to protest, but I couldn’t. I was a crybaby. If my mother walked in, I’d slide off my chair, attach myself to her legs, and beg her to do my homework with me instead. My father would tell her to leave, and she would, but only after telling him to “go easy” on me in a voice so flat that I realized she knew he wouldn’t. I’d crawl back to my seat feeling even more alone than before.

When we got to penmanship, my father pointed to the letter or word I was supposed to be copying, and to what I’d written below. “Does this look like that?”

I shook my head.

“Do it right.”

“I can’t.”

“You can,” he said. “Don’t be stupid.”

I tried again, but not really. I couldn’t think clearly.

“What’s wrong with you! You’re not even trying.”

I wailed, hoping my mother would hear me.

“Be quiet,” he finally exploded, shouting as loudly as I just had. “You’re such a crybaby!”

I hated myself for having so many flaws, and I tried to fix them. I filled countless black-and-white composition books with scribbly lines of “The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy old dog.” I made math flash cards and tried to memorize them. I hoped I could change into a child he would love.

The fear I felt around him was unbearable, and I started getting severe headaches. They happened at school most frequently, although sometimes they’d find me on weekends. They started behind my forehead and radiated around my skull. When they took hold, I’d whimper and rub my palms against my temples.

Questions from the school nurse led to questions from doctors. “Did you recently hit your head?” prompted me to remember that I’d knocked my head against a wall during recess the month before. I remembered the accident, but it hadn’t been bad. I’d gone to the nurse and gotten some ice and children’s aspirin. This was the only information they seemed to find helpful. I underwent CAT scans and other tests, but none of them revealed a problem. They weren’t migraines, there wasn’t a tumor. No one was sure what to do, and I detected a strain of suspicion beneath the questions. Were my headaches real?

They were. What brought them on was encountering difficult schoolwork such as new math or grammatical concepts, and my anxiety when my father saw me struggling to understand it. If I didn’t get something the first time it was taught, I believed it would stay hard for me. The pain felt like the result of my brain working really hard and swelling with stress. Succumbing to it was a way to push off the inevitable for at least a little while. My headaches were an exit, a way to not hear whatever was being taught, so I wouldn’t anger my father when he saw that I’d failed to master the lesson.

I wanted to tell my mother that I didn’t need to go to the doctor or lie in strange machines. I knew the cause of my headaches. It was obvious: I was stupid, my brain was broken. I didn’t think I could change, but I wondered if my father could. She saw how he approached the problem of his daughter, and how it failed to produce the result he seemed to want—a breakthrough or flash of understanding, a daughter he could be proud of, a daughter he could love. I wished he’d accept the failure that I was and leave me alone.

When I was ten, I was walking home from the playground with my friends Hillary and Shira, along with Shira’s nanny, a tired Irish woman whom I saw more frequently than Shira’s parents. I’d known Hillary and Shira since preschool—we lived in the same neighborhood and played together often—but Hillary and I were much closer than either of us were with Shira. We were best friends and fixtures at each other’s houses; she’d often come to New Hampshire with my family or I’d go to Martha’s Vineyard with hers. Shira could be bossy and a little mean, but her parents regularly pressured us into including her—or worse, spending time with her alone. Shira often made fun of me for not doing well in school. She also reported the things her parents said about me, such as their surprise when she’d told them that I wanted to be a zoologist—they couldn’t believe I wanted a career with such a complicated name. They thought their daughter was too good for me, but I was one of her few options.

As we made our way home, Shira’s nanny asked if I had any siblings, and I told her that I had an older sister.

Shira perked up. “You had a brother, too. But he’s dead.”

“No, I

didn’t.” I laughed and looked at her nanny. “I didn’t have a brother.”

“You did,” Shira insisted. “My mom told me.”

I was used to Shira making proclamations or correcting me with an adult’s authority, and I knew that she lied. We all did, if we wanted to win an argument about who owned the most pairs of jeans or to make one of our fantasies sound real. Shira was a mermaid like Madison in Splash because she ate shrimp with their tails on; I was a witch because I’d asked my cat Mischa if he was a witch’s cat, and he’d winked. But we lied about ourselves, not each other. I knew what she’d said wasn’t true, but I didn’t know how to prove it. I could call her a liar, but I couldn’t call her mother one.

“I did not,” I said again. “Stop.”

“You did have one,” Shira sang. “You did.”

Her nanny moved between us and said, “That’s enough, girls.”

There was something different about this lie: the outrageousness of the claim, the tone of Shira’s delivery, her mother’s involvement. It lingered among my thoughts until it was replaced by more immediate concerns, like what snacks were at home and watching ThunderCats.

Grandma Helen came to visit a few weeks later. One afternoon, she, my mother, Alexandra, and I were goofing around in my sister’s room, trying to recite a television commercial for long-distance phone service.

“Talk to your mother,” my mom said.

“Talk to your plants!” I shouted.

“No!” My sister laughed. “Call your mother, call your brother.”

Brother! The word summoned the memory of my conversation with Shira. I turned to my mother asked, “Did I have a brother?”

The question flew from my mouth like I was merely asking what time it was, but it landed with a thud and sucked everything in the room to it, including people’s smiles. Alexandra, my mother, and Grandma Helen exchanged uncomfortable looks. My grandmother and sister left the room, and my mother joined me on the edge of the bed.

I didn’t like what was happening or how it was happening: really slowly, but also really fast. The air was churning. I wanted to grab it and force it to be still.

“Yes,” my mother said slowly, “you had a brother. His name was Yuri. He was born after Alexandra, while we still lived in London. He died two months before his first birthday.”

I shut my eyes, found the edge of my sister’s mattress beneath her sheets, and held on to it. I thought I’d mastered my unsteady environment by teaching myself to expect disasters and danger, and to never relax. But that had only been training, and not a very good one. My mother had revealed that my immediate world was much bigger than I thought it was. It had a place, maybe many places, that I didn’t know about. They’d always been there, I just hadn’t been able to see them.

She guided me downstairs to her bedroom. I lay on the unmade bed while she collected two pictures of Yuri—one from the top of her dresser, another from its bottom drawer. The photograph on her dresser had always been there. In it, Yuri was around six months old, and Alexandra was offering him a red block as my mother beamed between them. I’d asked my mother who the baby was when I was very young, and she’d said his name, “Yuri. That’s Yuri.” She didn’t tell me that he was my brother or that he was dead. In the other picture, the one I’d never seen, he was only a few days old. He was asleep in a hospital nursery, and my sister was peering down at him through a large window. I recalled a picture in my sister’s photo album of my mother smiling over a double pram, and realized that Yuri had to be the other baby. He hadn’t been hidden from me, exactly, but his true identity had never been revealed.

I looked at the photograph that I’d seen before. It had changed. That baby was now my brother. I was older than he’d ever been, but I was his younger sister. “Brother” didn’t seem like the right word, since we’d never met. My sister had a brother, not me.

My mother explained that Yuri had died from pneumonia. She and my father were very sad when he died. My father had cradled his body and whispered “My son, my son, my son” as he wept. They’d been worried they wouldn’t be able to conceive again. “You were our miracle baby,” she told me. “Your father was hoping for another boy, but the second he held you, he was just so happy to have another child.” She stroked my hair. “We didn’t tell you about Yuri because we didn’t want you to feel like you were a replacement.”

She explained that she’d told Shira’s mother about Yuri, assuming they were talking in confidence. She wondered why Shira’s mother, a therapist and professor of psychology, thought it was appropriate to share the information with her daughter, who had “such a big mouth. But you shouldn’t be mad at Shira,” she said. “She didn’t know what she was doing.”

If there had been less agony in her voice, I might have been proud to be such a thing, a miracle, me. But I didn’t want to be one. I was so sad for Yuri. I wanted him to be alive, and I wanted to be normal. A dead baby was terrible; it should have been impossible. I felt haunted by his presence as well as his absence. He was there, and he wasn’t. He’d always been there, and I hadn’t known. I didn’t want to know about him. I wanted things to go back to the way they were before I’d asked my question, back to a way they’d never actually been.

We both cried, but I wanted to be the only one who was upset. My mother’s pain indicated yet another world, one that was hers, one I didn’t want to be in. If she needed comfort too, she wouldn’t be able to take care of me. If she was that vulnerable, I was even more helpless and alone than I’d previously felt.

She told me that she was still sad about Yuri and thought about him every day. Then she shared a story. She’d once accompanied my father to dinner at his colleague’s house in Zimbabwe. Afterward, the men went to smoke cigars and discuss work and politics, while the women drank tea and talked. The hostess complained that her maid was taking time off because she’d lost a child. My mother suggested that this woman might have some sympathy for her employee, and the woman said, “These people are used to losing children. It isn’t a big deal to them.”

“I wanted to strangle her,” my mother said. “To slap her and say, ‘How dare you? A mother never gets over losing her child.’ ” Although my mother loved showing me pictures of her trips and things she collected abroad, she didn’t tell many long stories about what happened when she was away. Once this story had been introduced, it joined the canon.

My father was out of town when we had this talk, and though I assumed that my mother told him about it, he never spoke of Yuri to me. I found myself looking for Yuri over my shoulder, wondering if he’d always been following me, hiding under my bed or in my desk at school.

On a Sunday morning a few months later, while my family was spending the weekend in New Hampshire, my mother told me to eat breakfast quickly because we were going to church.

I looked up from my yogurt. “Why?”

“It’s the anniversary of Yuri’s death,” she said. “Try to find a nice shirt.”

I put on a fuzzy green sweater that had once been Alexandra’s, the nicest thing I had in my collection of ski clothes, and zipped up my parka until the old lift tickets scraped my chin.

We went to a small brick church on the outskirts of the closest town. It was more like an office building than Boston’s dramatic churches, which had spires, turrets, and stained-glass windows. It was a regular Sunday service. Families clustered in the middle of waxed pews, and people who’d come alone sat in the back or close to the aisle. I stood, sat, knelt, and said “Amen,” but I didn’t listen to the priest. I thought about how bored I was, and that I was cold, and wondered what we’d eat for lunch. Maybe we’d go to the town’s one restaurant, since it was kind of a special occasion. Maybe I’d be allowed to get a sundae.

My attention was pulled back when I saw that the empty pew in front of me was shaking. I glanced at my father; he was clutching the back of it and convul

sing with grief, his mouth contorted by gasps and groans. His pain was louder than my mother’s had ever been. It wasn’t pleading; it was violent. I shrank against the pew, horrified by his transformation. Like my mother’s grief, his also scared me, but in a different way. Hers made me think that she might not be strong enough to ever be relied on, but his made me wonder what else he could do to me.

When I looked at him after the service, he was back to normal, but I knew that whatever force had overtaken him could come back. I thought that if I could examine his insides as I had my own, the X-ray would reveal that a calcified deposit of melancholy held his body together and not a frame of bones.

We didn’t go to the restaurant. We drove the twenty minutes back to our cabin and each claimed our own space. I sat in the loft where my sister and I slept on the long, checkered futon that Velcroed together to make a couch, and put a book I’d already read in front of my face.

Thinking about that morning in church made me so uncomfortable that I batted its images and sounds away as if they were flies. I tried to do the same with the conversation I’d had with my mother. I didn’t want to think about that, either. All I knew was that a change had occurred because a truth had been exposed. Not only did I have a dead brother but my parents had secrets, and I didn’t know everything about the world we shared. We were operating with different maps. Mine had blank spaces, entire continents I’d never heard of.

My life was the same, but I was different. I was listless and morose. I didn’t attach these feelings to learning about Yuri as a person, my brother, a fact or event. I didn’t attach them to anything, so they grew without my help or awareness as I wandered through my days. My father still yelled at me about homework, but my reactions, and my efforts to make him happy, were dulled. Only my headaches were sharp.

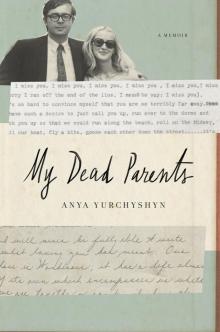

My Dead Parents

My Dead Parents