- Home

- Anya Yurchyshyn

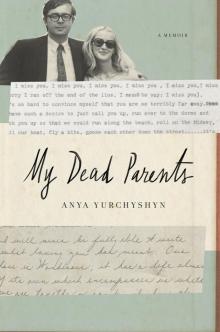

My Dead Parents

My Dead Parents Read online

This is a work of nonfiction. Nonetheless, some of the names of the individuals involved have been changed in order to disguise their identities. Any resulting resemblance to persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental and unintentional.

Copyright © 2018 by Anya Yurchyshyn

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

crownpublishing.com

CROWN is a registered trademark and the Crown colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 9780553447040

Ebook ISBN 9780553447057

Cover design: Elena Giavaldi

Cover photographs: (parents) courtesy of the author; (typed letters) George Yurchyshyn/courtesy of the author; (handwritten letter) Anita Yurchyshyn/courtesy of the author

v5.2

ep

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Part One

Introduction

Chapter One: Unhooked

Chapter Two: Ghosts

Chapter Three: Ukrainian Death

Chapter Four: My Mother’s Waltz

Part Two

Introduction

Chapter Five: Secret Garden

Chapter Six: Kiss of Fire

Chapter Seven: Mountains

Chapter Eight: Shamefully Happy

Chapter Nine: Unternehmungslustig

Part Three

Introduction

Chapter Ten: The Painter’s Honeymoon

Chapter Eleven: The Giant’s Seat

Chapter Twelve: Ukrainian Death: Part Two

Afterword

Acknowledgments

About the Author

“Whereas the beautiful is limited, the sublime is limitless, so that the mind in the presence of the sublime, attempting to imagine what it cannot, has pain in the failure but pleasure in contemplating the immensity of the attempt.”

—IMMANUEL KANT

НА КОНЯ!

(Onto the horse!)

My mother, Anita, died in her sleep in 2010, when she was sixty-four and I was thirty-two. The official cause of death was heart failure, but what she really died from was unabashed alcoholism, the kind where you drink whatever you can get your hands on, use your bed as a toilet when you can’t make it to the bathroom, and cause so much brain damage you lose the ability to walk unsupported. The cause of her death was herself, and her many problems.

The month after she died, I began cleaning out her house, my childhood home, in downtown Boston. As a kid, my house sometimes seemed enchanting, filled to the ceiling with items my parents had collected on their many trips around the globe. But when my father, George, was killed in a car accident in Ukraine in 1994, my mother lost interest in our home, and it started to die as well. By the time she passed away, treasured rugs were being eaten by moths and mice, the fire escape was dangling off the back, and some windows wouldn’t open, while others wouldn’t close. Everything that once seemed special was chipped or cracked and buried under sticky dust. I saw cleaning out the house as my last goodbye to her and my dad, and I was eager to finally be rid of them. I thought I would box up what I wanted, toss what I didn’t, and avoid being caught by what had become its most potent force—sadness.

My parents were intellectuals with exciting careers, but that wasn’t what mattered to me as their child. My father had been emotionally distant and occasionally abusive. My mother hadn’t protected me. She was resentful and selfish, and this was before her drinking brought out, or created, qualities that were much worse. My parents were married for twenty-seven years, but rarely seemed to even like each other. I believed that they’d never been in love.

I began my work in my mother’s large study. Growing up, it had been the part of the house that was specifically hers, an area where the air was still and sacred. It was where she wrote and practiced her speeches for the Sierra Club, kept her favorite books and special jewelry. But during the last ten years, it became a haphazard storage room for everything from stained sheets to months of unopened mail. I spent days sorting the clothing piled on the room’s red couches and the incredible amount of panty hose she’d purchased from Filene’s Basement and never worn. I’d anticipated this task for years, and getting rid of things so banal and expected was both boring and surreal: There goes that stained cotton turtleneck, that long pink coat she made my father buy her because she thought it made her look regal.

I split the wall of books between boxes that would be donated and boxes that I’d bring back to Brooklyn. I reached deep into her closet and, when I came across something that my sister and I might want to keep—silk kimonos, a leopard jacket—I brought it into my mother’s room and placed it on her bed, which had been stripped by her aide the morning she’d been found dead in it.

I tried to summon a memory of getting rid of my father’s belongings after he died, but couldn’t. Then I remembered that my mother’s best friend, Sylvia, had traveled from Chicago to help with the job, sparing me from having to fold his suits and throw away his underwear, and from seeing my mother doing it. Although the house had been my parents’ and they’d acquired the majority of its contents together, I’d gotten used to thinking of it as my mother’s. What I was going through those first few days was the soggy life she’d lived after my father died.

Once I’d pried loose this first layer, I began to move more slowly. I had to pay attention to what was passing through my fingers—my mother’s work files, broken necklaces with beads my sister might want to repurpose, our grade-school report cards. At the bottom of a small wooden chest, I found a collection of letters bound by a cracked rubber band. After I’d managed to remove it, I unfolded the letter on top of the pile. It was typed on thin, crinkly paper, dated 1966, and addressed to my mom, who would have been twenty-one.

I miss you, I miss you, I miss you, I miss you, I miss you, I miss you, I (sorry I ran off the end of the line, I meant to say: I miss you). It’s so hard to convince myself that you are so terribly far away. I have such a desire to just call you up, run over to the dorms and pick you up so that we could run along the beach, roll on the Midway, sail our boat, fly a kite, goose each other down the street…

I laughed. Who’d write such goofy things to her? I scanned the pages that followed, but it was only the signature, handwritten in blue ink, that revealed the author’s identity: George. “What?” I whispered. My father would have never written such silly things or have been so free with his affection.

I made my way through the rest. In 1971, my father wrote, “Whenever I leave you I feel a powerful and wonderfully terrible series of emotions…there is an emptiness inside me, a true aching of the heart. It is a longing and a dull sorrow for leaving behind that which I love.”

In 1973, my mother told him that she’d “never be fully able to write what loving you has meant. Our love is wondrous; it has a life almost of its own which encompasses us whether we are together or apart.” Her tight, Catholic school script was barely legible, but the ink was steady and bold. She’d transcribed her devotion in a fever. When I flipped the page over and ran my fingers across it, I felt the force of the words she’d pressed into it.

What I was reading contradicted what I’d long ago decid

ed: that my parents had never been happy with each other, never had hope. I couldn’t believe that my father could have been so articulate and vulnerable, or that my mother had ever adored him so intensely. My brain was in revolt. What I was reading seemed to have been written by strangers, not the people I’d known. I read their letters again and again, arguing with what I found. But as I continued to find proof of their love, I realized that I was defending the story I’d arrived with against mounting counter-evidence, and losing.

There were many more letters, as well as postcards, faxes, and trunks full of pictures and slides. Each offered a window into my parents’ lives and revealed parts of them I’d never seen. Almost every year of their relationship was accounted for in their own words. It was intimate and foreign territory, unfathomably vast. The space I’d cleared had filled up again; the whole house could not contain everything I didn’t know.

I sat in my mother’s study for days, trying to take in my parents’ lives and relationship, to see them for who they really were. When my sister called to ask how the cleaning was going, I cheerfully said “Great,” but it had come to a sharp stop. I was picking at our parents’ remains like a vulture, more concerned with what I could consume than what I should discard.

I had so many questions, and I couldn’t ask my parents any of them. I wanted to wave their letters in their faces and shout, “Hey, what the hell is this? And what the hell happened to you?”

I searched and gathered and read and reread, until I slowly began accepting what was so obviously true: I didn’t know my parents at all. The stories I’d told myself about them were wrong. Instead of pushing them away as I’d planned, I worked to bring them closer, hoping I could learn who they’d really been and what had happened to their love.

My parents traveled with empty suitcases. Black, with stiff plastic shells, their luggage was scuffed and dotted with stickers from airports around the world. These suitcases banged hollow against the ones that held my parents’ clothes as they hurried out of our Boston home to their next destination, where they knew they’d fall in love with objects large and small. The suitcases were heavy when they returned weeks later; sometimes it took both of them to carry one.

The night they came back from wherever they’d been, they gathered my sister, Alexandra, and me in the living room so we could watch them unpack their new treasures. My father unfolded a coarse rug and said he’d spent six hours drinking tea with its seller in Lebanon. My mother held up a statue and said that the dealer who’d sold it to her in Zimbabwe had tried to swap it with a fake when he delivered it to her hotel room. A small embroidered hat was placed on my head; it had belonged to the son of a Syrian imam. These unveilings happened so frequently throughout my childhood that eventually they looped into a single evening, one longer and more interesting than any day, where my parents talked over each other, shared jokes my sister and I didn’t get, and delighted in their acquisitions as well as in each other. My father traveled more than my mother, and when he returned from a trip he’d taken alone, he’d make a similar presentation. But those evenings lacked the intimate electricity of the ones that followed a trip they had taken together.

As my mother studied their purchases, she sucked on a Kent Golden Light and sipped a martini that dangled loosely from her hand. She’d crouch down and ask my sister and me what we thought of the things we were seeing, while my father remained upright with his hands on his hips and a smile on his face. We gave our assessments: pretty, ugly, scary, weird. As we spoke, they found a home for each new prize above the fireplace or on a chest, situating a Chinese snuff bottle between an Afghan dagger and a Hopi basket. I’d fall asleep on the floor before they finished unpacking, sprawled on a rug procured on an earlier excursion, momentarily happy, and even grateful, to be their child.

Our house was a cramped testament to my parents’ curiosity. There was no television in the living room, but there was an African statue in every corner, Iranian kilims and Indonesian textiles hanging off every wall, and shelves crowded with books. I had little knowledge of the context or craftsmanship of what my parents collected, but each item gave me a jolt when I touched it. They were all from the same place: far away. I couldn’t wait to get there.

My father took his battered Nikon camera and at least ten rolls of slide film on every one of their trips. A few days after their acquisitions were unveiled, the four of us gathered again in the living room as he fought with the slide projector, fussed with the carousel, and steadied the pull-down screen on its stand so Alexandra and I could see where they’d been.

In the dark of our skinny row house a few blocks from the Charles River, he showed us ancient cities, rain forests, market stalls with pyramids of bright fruit. My parents smiling as they rode camels or held each other in front of an ornate fountain. My mother alone as she glanced seductively at my father or into the distance with a look of humble contemplation. Attuned to the distinct vibrations of my father’s silences, she knew when he was plotting a candid photo and made sure he got her best angle. When we came to a picture of my mom bathing under a waterfall or perched on a desert rock, my father paused the show. He’d remove a bunch of slides and study them in front of the projector’s lens, put a few back in, but set more to the side. Pictures of my mother usually came in a series; with each photo that clicked by, pieces of her clothing disappeared.

During these presentations, I looked at the people in the photographs, at the people showing them to me, then back at the pictures again, searching for glimpses of my parents in each. The couple in the room and the couple on the screen matched only in the days after they returned. When the slide show was over and the projector put away, this couple transformed back into people I recognized; they became my parents again. The cozy bubble had popped, and life would return to its normal state. I’d go back to looking over my shoulder, to shuffling through the house in fear.

When I wanted to travel, I studied copies of National Geographic or went on “safari” in our Junk Room, where items not currently on display, or that my parents had forgotten they owned, were stored: wooden masks too scary to touch, knives with horn handles, a shrunken head with hair on it. The overhead light had burned out long ago, and boxes and trunks were stacked so high that the thin beams of sunlight that shot between them could only lift the musty dark to dusk. Entering the Junk Room was like pushing through Lewis’s wardrobe and finding myself in Narnia. I was on an adventure in a mysterious world, one where I saw myself whacking through thick jungle vines and creeping into forgotten tombs. My expeditions were more frequent than my parents’, but I could always discover something new by creating a fresh path or having grown the inch necessary to finally be able to reach a certain shelf. When I heard them calling my name, I returned, covered in scratches and dust, and unsure of how much time had passed.

A desire for adventure wasn’t the only reason that I set off into the Junk Room; I also went there to hide from my father. My father as I knew him wasn’t the man in the pictures, a man who was relaxed, happy. He was a bully with a temper as destructive as a wildfire, one I seemed fated to spark. He was the commanding force in my life. His moods controlled its weather; his words crushed and corralled me. To him, I was always doing something wrong, and that made me so nervous that I’d inevitably trip or slip, drop glasses and plates, fall out of chairs. At any moment, I knew I could do something to ignite his anger and he’d unleash a storm of insults: messy, clumsy, stupid, a crybaby. I was an emotional, skinless kid, and his words, delivered with rage or in whispered disgust, hurt more than any physical punishment.

A small child in a family of small people, I spent my youth not wanting to be bigger but to be smaller still. I wished I could be absorbed into walls, contort my limbs to fit through mouse-size cracks. I hid in the dark of the Junk Room and in my closet but was never able to make myself fully disappear from my father’s radar. I was terrified of his rage and hated that he saw my tears

as a reason to yell more, not less. Though my mother was affectionate and never yelled the way he did, I was scared of her as well, because she didn’t, or couldn’t, protect me from him.

If I had to be near my father, I’d unhook my heart and retreat to a secret place within myself. My eyes still blinked, and I could answer questions when asked, but I wasn’t really there. I thought that he wasn’t angry about whatever bad or stupid thing I’d done; he was angry because of me. I was the bad thing that had happened, the thing that was wrong. My simple, stupid existence was the problem. I thought he’d correctly determined that I was innately deficient, too broken to fix. I knew that it was mean to yell at me the way he did, but I also thought I deserved it. How frustrating for him to be burdened with such a defective daughter.

When I was two, I fell down the flight of wooden stairs that led to our kitchen, tumbling over and over until my face hit the landing.

I’d been looking for my parents, who were drinking coffee and eating grapefruit. My father ran over as I howled. He lifted me to my feet and shook me. “What’s wrong with you, dummy? Don’t you look where you’re going?”

I put my hands on my hips and shouted, “Don’t call me a dummy,” then ran to my mom and took shelter in her robe.

I don’t remember this moment, but my mother spoke of it many times. She’d do an impression of me, scrunching her face in anger, stomping her foot, growling “dummy.” She was proud that I’d stood up to my father, who was shocked by the force of my response. I was shocked by it, too; I never defended myself, never yelled back.

A moment I do remember: I am four and in the pantry, a tight space off the living room where my parents stored alcohol and plates reserved for company. The pantry had a stove that was different from the one in our kitchen. It was flat and embedded in a countertop. I was playing with it as my parents prepared for a dinner party, grabbing its knob and turning it hard enough so the button went red. My father told me to stop, then told me again, and again. He said it was dangerous, to leave it alone, that it was something only grown-ups could touch. Anya! What? Stop!

My Dead Parents

My Dead Parents