- Home

- Anya Yurchyshyn

My Dead Parents Page 2

My Dead Parents Read online

Page 2

I couldn’t. I was too mesmerized by how the metal got hot without any fire. He stalked over and grabbed my hand. I watched as he pressed my finger to the stove’s shiny surface. When the pain hit, I screamed. My mother ran to me and screamed, too, but that didn’t make him stop. When he finally released my finger, he flipped over my hand, and we watched the blister form and fill.

I wrenched my wrist from his grip and took off for my room, where my mother soon delivered an ice pack and a stack of Oreos. I stayed quiet. I wanted the Oreos, but I didn’t want to need them, or an ice pack, either. My father had taught me the lesson he’d wanted, and a few more I wouldn’t forget.

Alexandra, who was five years older than me, never seemed to provoke his anger the way I did—further proof that I was the problem, not him. Sure, he yelled at her, but not like he did at me. The reason was obvious: She was smarter and better behaved. And prettier. And cleaner. She had long, straight brown hair. I idolized her because she was older and had a room full of barrettes and magazines. When her friends came over, I’d sit outside her bedroom and whine until my mother forced them to play with me. But I didn’t consider her an ally; I resented her ability to avoid our father’s wrath, and for not crumpling under it like I did.

I wasn’t afraid of my dad all the time. When he came home from his job at the Bank of Boston and shouted “I’m home,” I ran to him almost as often as I ran from him. The direction depended on how recently and severely I’d been shouted at. If it had been a few days, I’d jump up and down while he took off his black coat and stood in the living-room doorway. I’d hop on one of his legs and wrap myself around it, and he’d swing me back and forth until his foot cramped. On many weekend mornings, I’d creep into my parents’ dark room, made hot by their bodies, and slither into their bed. I’d climb on top of my father, who pretended to be a raft on the “great, grey-green, greasy Limpopo River” from Kipling’s Just So Stories. As I balanced on his belly, he’d rock back and forth and identify the creatures he saw on the river’s edge: cheetahs and crocodiles, hippos submerged to their nostrils. I’d inevitably hit a patch of rapids, and if they didn’t succeed in capsizing me, a current I couldn’t fight sent me over a booming waterfall that dumped me onto the floor.

My father also took my sister and me skiing in New Hampshire, where we had a small cabin that my parents had decorated with Native American and Western antiques. Wherever we were, if we found an arcade, he’d spend ten bucks playing Centipede and Skee Ball with me. If we couldn’t get a good-enough prize with the tickets we’d earned, he’d offer up ten more. At Christmas, my father was usually able to control his temper for at least two days, which led me to think that the holiday, its decorations and traditions, might have magic powers. But those easy moments were erased by the ringing chaos that normally engulfed me.

I studied my small world and wondered why my parents were the way they were. I thought that they, my sister, the people down the street at the 7-Eleven orbited around only me. If my parents left the room, or I ran out of it, they froze in place. They haunted my thoughts, but they didn’t continue living, acting, or being acted upon, and had come into existence when their children did.

I knew only the most basic elements of their lives. My mother worked; she did something with oceans and also maybe trees. Later I understood that she was the international vice president of the Sierra Club. Her position was unpaid and allowed her to work from home, but she traveled often to the club’s headquarters in San Francisco and attended environmental conferences all over the world. She stood out in our WASP-y neighborhood with her multicultural collection of jewelry and clothing, and the cigarette dangling from her mouth. I thought she was beautiful. She was petite and blond, and she carried herself like a model though she had crooked, tobacco-stained teeth and a mole on her chin.

One of her favorite pieces of clothing was a black silk bomber jacket that she’d gotten in China, which had a fire-breathing dragon embroidered on its back. When she wore it to pick me up from nursery school or kindergarten, other kids would shout “Dragon Lady!” They’d turn to me. “Your mom is here. The Dragon Lady is here.”

I’d demand they shut up, but they weren’t scared of me, only of my mother. When she opened the gate to the playground, they’d stop. As we walked home, she held my hand in her left and a cigarette in her right, and I’d pull on her arm.

“Don’t wear that jacket anymore,” I’d beg. “Kids make fun of me. And you.”

“Well that’s not nice, but you should just ignore them.”

“I can’t!” I’d wail.

She laughed. “This jacket is very chic, Anya. I’m wearing it.”

Though I hated that kids joked about my mom, I loved how she dressed and that she was different. My mother didn’t do a lot of things that my friends’ mothers did. It was my father who helped my sister and me get ready in the morning, who fed us and walked us to school. My mother spent her mornings sleeping, snoring loudly behind their bedroom door. I accepted that my mother slept late, just as I accepted that, if I had a nightmare, it was my father who arrived to comfort me with a Ukrainian lullaby, although the person I’d been crying for was my mother. I was attentive to the nuances of gender at a young age and understood why she rarely cooked or cleaned; it was boring. The few times the four of us ate dinner together, my father would end up screaming at my sister and me because we were slow, fussy eaters. Sometimes he chanted “Chew, chew, swallow, swallow, faster, faster,” or turned off the light and left us to eat in the dark after he and my mother had finished and gone upstairs.

When he was away, and sometimes when he was home, my sister and I were in charge of feeding ourselves. At five and ten, we became experts with can openers and microwaves so we could eat our Chef Boyardee and Hungry-Man dinners. I wasn’t mad that my mom didn’t cook. I hated eating with my family and preferred eating alone. I would have swapped my parents for a completely new set if I could have, but since I couldn’t, I liked being able to avoid them.

My mother’s style matched her personality. When she and I ran into someone she knew, she laughed extra hard and rolled her eyes or hugged me tightly like a mom in a happy family sitcom. She was always telling stories and constantly repeated ones that I, and the rest of her audience, had heard before. Her best bits supported her two most important beliefs about herself: that she was a wonderful person and mother, and that she was a victim who’d suffered many injustices. The first relied on her tales of how, when she was a teenager, a stranger had spat on her Jewish friend, and she’d righteously stood up for him; and of how when Alexandra was three, she told her that “it doesn’t really matter what color you are, just what kind of person you are,” and later heard my sister singing those lines to herself in the bath.

Strangers often complimented my name or said they’d never heard it before. If my mother was around, she’d chirp, “Thank you, I made it up.” I believed her until I met another Anya in a pottery class when I was eight. I told my mother about it, but she dismissed me before I could ask all the questions that I suddenly had. She continued to tell people that she’d come up with the name herself, poof! When I later found a novel on her bookshelf with my name as its title, I brought it to her and waved it indignantly. “You didn’t make up my name. This book is called Anya!” She told me it was a coincidence. I kept at her, desperate to have her admit she’d been lying, but she wouldn’t give in.

Realizing that my mother lied took away not only her credibility but my belief that she was special. It suggested that she thought she needed to be more, a better woman than she was. I wondered why she had to tell her stories over and over. What was she asking of me, or her other listeners, by repeating these anecdotes until we could recite them along with her? She never even seemed to consider how they might land; she thought the meaning or moral that was obvious to her was what we’d take away, too. But that wasn’t true of the story of me falling down the sta

irs. From that, I got not that I was brave but that when my father was cruel to me, my mother didn’t stop him, a conclusion that was solidified when my father burned me.

Although she smiled and laughed a lot, I didn’t believe my mom was happy. She looked like she was performing joyfulness, not feeling it. At home, I saw a cloud hovering around her, and even when she was with people, I could sometimes see loneliness in her face when she glanced away or the light shifted. She was quick to obscure these shadows with a joke or a bark of laughter, but something trembled within her, and I didn’t trust whatever it was.

The stories about the injustices of her life were even more practiced, such as the one she often told about the visit she made to her father, Roman, when she was twelve. He’d been in and out of mental institutions and had abandoned his family the day after my mother was born. When she appeared on his doorstep years later, he told her to leave. He and his new wife had company, and their guests didn’t know about his other family. The first few times I heard this story, I was sad for my mother. Her dad was “crazy” and so mean he wouldn’t even let her inside his house. Tales like these were presented less like stories than requests, or sometimes demands, for sympathy.

Though she was articulating one of the sources for the pain I’d glimpsed, I didn’t believe that Roman was responsible for it. The explanation I chose was my own father. He was the reason for my heavy unhappiness, so I decided he was also the cause of hers. My mother broadcast her craving for attention and affection to him as often as she did to others, but he always seemed too uninterested or distracted to respond. She would talk to him with need or frustration in her voice as he frowned and leafed through whatever stack of papers he’d brought home, until her sentences trailed off into an exasperated “George!” My mother seemed to accept their dynamic; to me, this was further proof that they didn’t love each other, and that my mother was weak.

A few days before Halloween, when I was eight, my father tried to help me carve a pumpkin. We fought about the design, and when I didn’t give in, he dropped the knife abruptly and left the room. Having failed as a referee, my mother let me crawl into her lap and drench her shirt with tears.

“Mom,” I whispered, “sometimes I don’t love my daddy.”

“That’s all right,” she said. “It’s not always easy to love people.”

I thought she was speaking to herself as well as to me.

I watched my father as closely as I did my mother but knew even less about him. I knew that he worked at a bank in a tall building downtown, and that his job was the reason he traveled so often to the Middle East and Africa. Though he sometimes made jokes, overall, he was serious. His skin and hair were darker than mine; he wore silver glasses and had a short, coarse beard. He wasn’t tall, but to me he seemed huge.

Besides his temper, my father’s most obvious attribute was that he was Ukrainian. He’d been born there and spoke the language with his parents and friends. I knew I was also Ukrainian, but only half, because my mother was Polish American. Being Ukrainian meant that my family made varenyky and borscht from scratch on Christmas; painted pysanky, the traditional Ukrainian Easter eggs; and went to a Ukrainian church on both holidays. Occasionally my father tried to teach me a bit of the language using cheap picture books, but he always gave up when I couldn’t pronounce any of the words correctly or retain them. These details amounted to what being Ukrainian meant to me, but I didn’t know what it meant to him.

My father told me three stories about his childhood. Unlike my mother, he only told his stories once. They all happened in Ukraine, where he was born in 1940 and which his family fled four years later. Two were about being attacked by farm animals, and one was about his family’s rushed escape from their village in a horse-drawn cart. I couldn’t conjure an image of his family’s escape, a cart, danger. It didn’t seem real and neither did Ukraine. Ukraine sounded like a setting for a dark fairy tale that offered no magic or redemption, a place that had nothing to do with me.

I learned much more about being Ukrainian from my father’s younger sister, my aunt Lana; her husband, Gene; and my younger cousins, Larissa and Natalie. We spent holidays and occasional weekends at their home in Connecticut. Unlike my father, Lana married a Ukrainian, and their daughters were raised with a strong sense of cultural identity. When my grandfather Dymtro, whom we called “Did,” died, my grandmother Irene, “Babtsia,” moved in with them, and she contributed to and monitored the household’s Ukrainianness.

Larissa and Natalie seemed foreign because they were so Ukrainian. They’d grown up speaking the language, going to a Ukrainian church, and attending Ukrainian scouts and summer camp. From them, I concluded that being Ukrainian meant being purposely distinct and dorky. I felt lucky that my father had raised me differently, but when my sister and I were with Aunt Lana’s family, I noticed that he compared us to our cousins and that we didn’t measure up.

Every Easter, as my father drove us to Connecticut for church and my aunt’s traditional lunch of kovbasa, eggs, and babka, he’d drill us on the appropriate Easter greeting: “Khrystos voskres” (Christ is risen!), and its response, “Voistynou voskres!” (Indeed, He has risen!). We’d not only forgotten it from the year before but still couldn’t get it right. He’d become more frustrated with every mile, repeating “Khrystos voskres! Voistynou voskres!” over and over as we sank into our seats and mangled the words. He’d slow down so he could safely drive while looking back at us, shouting “Khrys-tos vos-kres!” while my mother begged him to focus on the road. We’d have the phrase down when we pulled into my aunt and uncle’s driveway, but we’d forget it by the time they opened their door. We’d mumble distant approximations until our father groaned and pushed us inside.

Babtsia was sweet to my sister and me, but she never missed an opportunity to remind us that we should speak Ukrainian like our cousins, who were the products of an appropriate union. She treated my father like a visiting dignitary; after giving him a formal hug, she sat him on the couch, brought him coffee or water and a plate of food, then sat close by and asked about his work, his take on current events. She was polite to my mother but rarely pleasant. My mother had told me that his parents had opposed their wedding and threatened not to attend because she was Polish. I didn’t know why that was so important to them, or what risk they thought my father was taking or fate they believed he was courting by committing to my mom. I wouldn’t find out until many years later.

In my memories of childhood, my father was always around, working at our long living-room table, reading an American or Ukrainian newspaper on the couch, or screaming at me. He felt inescapable. In truth, he was often gone—to Nigeria, Zimbabwe, or Turkey—for weeks at a time. My body relaxed in the easy quiet that settled in our home. My mom and I watched reruns of Cheers and I Love Lucy as we lay on their bed, and I could run through the house without being yelled at. I looked forward to my father’s departures, but when my mother was going away for Sierra Club work, I’d follow her around hiccupping from the fear. I didn’t want to be left alone with my dad. When she was traveling, he was even harder on me and even more difficult to avoid.

When my mother was able to join him, or when they just wanted to travel together, my mother’s mother, Grandma Helen, came from Chicago to stay with us. She was the person I loved most in my family. She wore soft cardigans and faded housecoats, and padded through our house in pink slippers. She played endless games of Connect Four and Scrabble with us, and made us Wheatena for breakfast. Babtsia babysat us only once. I don’t remember what happened, but my mother told me she demanded they come home early because we were so wild.

I didn’t miss my parents when they were gone, even when their trips were almost a month long. Their absences were normal to me, and they felt like vacations, a break from shouting and fighting, and hiding.

Sometimes when my father was away alone, my mother’s friend Bob would visit. She was girlis

h in his presence and seemed genuinely happy when he was there. I was happy, too. I adored Bob because he was funny and affectionate and never got angry. I wished I had him as a father instead of my own.

Once, when he and my mother were trying to get me to nap, I threw a tantrum because I didn’t want to stop hanging out with them. I started stomping my feet, and Bob tried joking with me. He said, “Do you want to have a stomping contest?” and started stomping, too. He and my mother laughed, and I began to cry. I understood that they wanted to be alone and to have fun without me. After he left, my mother asked my sister and me not to tell my father that Bob had stayed with us. She made the same request after each of his visits.

My mother enjoyed her prettiness and the attention she received for it, as well as for her flamboyant style, but I looked like an urchin. I’d inherited my parents’ terrible vision. Both of my eyes were weak, but one was even weaker than the other, and I began wearing thick glasses in kindergarten. Far more embarrassing was that I sometimes had to wear a flesh-colored eye patch to strengthen my weaker eye and prevent it from becoming permanently turned in. Adults and children gawked at me when I wore it in public, and I would become so upset that I’d remove it and throw it on the ground. One of my parents would be prepared with an extra and would press it on as I protested.

My hair was dark, somewhere between curly and wavy, and my mother kept it short. I envied my sister’s long hair because she could wear pigtails and barrettes, and because it told strangers that she was a girl. They often thought I was a boy, and addressed me as one. “I’m not a boy,” I’d wail as they went red and apologized.

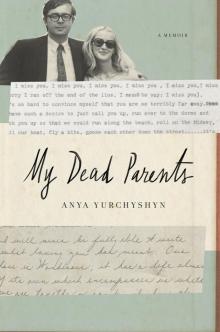

My Dead Parents

My Dead Parents