- Home

- Anya Yurchyshyn

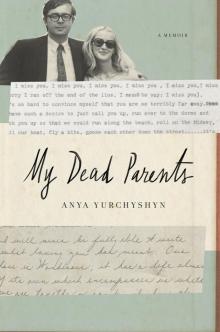

My Dead Parents Page 5

My Dead Parents Read online

Page 5

I liked pushing boundaries, but I wasn’t good at dealing with the name-calling and rumors that resulted. I wanted people to like me, and when they didn’t, I became impulsive, then explosive. I’d had to swallow so much rage in front of my father; I couldn’t hold it in anymore. And since he was gone, I felt free to express all of it, but I wasn’t in control of what erupted. Anger at him, at my mother, anger at everyone and everything.

One weekend, I had a friend over. Chloe wasn’t very cool, but I was happy to have a friend for a bit and liked that my mother didn’t like her. I’d gotten some fireworks on a trip to New York, and I decided that we should light one and toss it out the window.

My mother heard the noise and started screaming my name from the kitchen. Chloe and I went downstairs and found my mother cooking. She yelled at me about how dangerous what I’d done was. I knew she was right. If I’d bothered thinking about it, I wouldn’t have done it. But I hadn’t. I apologized, but she wasn’t done. She turned her anger on Chloe, who was standing silently next to me. “You always do something bad when she’s around.”

I was incensed that she’d attack my friend. “It was my idea,” I said. “Not hers.”

She didn’t seem to hear me. Her eyes were fixed on Chloe, who was looking at the ground.

“It wasn’t her fault. Apologize to her,” I said.

My mother refused, and said that Chloe needed to call her parents and have them pick her up. Chloe looked at me nervously.

I felt protective of Chloe, who like me wasn’t popular with kids or their parents. I knew my mother was echoing things she’d heard before. “Say you’re sorry.”

My mother said no.

There was a long knife on the counter next to a stack of carrots. I picked it up and pointed it at my mom.

“Say it,” I hissed. I held it firmly while my mother and Chloe stared at me. It made me feel powerful, as did the terror twisting my mother’s face.

“Put that down,” she said quietly.

Again, I told her to apologize. I needed her to make the situation right. “Do it.”

She did. I placed the knife back on the counter. Chloe’s parents picked her up, but my mother didn’t talk to them. I spent the rest of the night in my room blasting Mötley Crüe and feeling satisfied. I’d gotten what I wanted. I could hear my mother talking on the phone in the quiet between songs and felt safe knowing that she wasn’t talking to my father. She couldn’t get in touch with him. We never spoke of that incident, and though I’m sure she told my dad about it, he never brought it up. Neither did the school psychologist. I took this to mean that I’d successfully asserted my power, and I thought I was done with being bullied. Years later, I learned from Aunt Arlene, my mother’s sister, that my mother had told her, and many other people, about what I’d done, and that I’d terrified her.

When my father swept into town after weeks in Ukraine, he saw that our lives in Boston were continuing in a way he didn’t like. Alexandra had started college in western Massachusetts, so it was only the three of us. He’d try to impose order, reinstate the rules and structure that my mother had abandoned. He didn’t care that my hair was always a different color or that I wore pounds of dark makeup and combat boots, but he hated how bad my grades were and that my mother was obviously not doing enough about it. He’d tell me when I had to be home and when I could or couldn’t go out, reminding me that I wasn’t actually free of him. I raged to myself when I encountered his obstacles, but I suffered them because I knew they’d disappear when he did.

I still didn’t know anything about his job. I didn’t ask what he did; instead, I asked my mother when he was leaving. I also didn’t ask about the strange things that appeared in our house, including enormous boxes of kupon, the interim currency that my father helped develop to replace the ruble. Inflation in Ukraine was so rapid that the kupon was near-worthless upon printing. It looked like Monopoly money and was barely more valuable. My sister and I would throw fistfuls of it in the air and at each other when she was home on break, fill our claw-foot tub with them so we could bathe in money and pretend we were the richest kids in the world, and try to pay with them at the 7-Eleven down the block.

That year, my father left his position at the National Bank of Ukraine after a year and a half. When I asked my mother why, she simply said, “Corruption.” Instead of returning to Boston as he’d promised, he established the first venture capital fund in Ukraine with the help of one of our neighbors, David, who ran such funds in China. My father promised my mother it would only be a few more years of back and forth. His plan was to make the fund successful enough that he could manage it from Boston.

In eighth grade, life at school became particularly bad after a new friend I’d had for almost a year turned against me and went after me ruthlessly. She and another girl took markers to the bathroom and wrote all over its walls and stalls that I was a slut; the school had to close the bathroom for a week so it could be cleaned. The following month, she stole my copy of the script for a play I was in and wrote the same thing on its pages. Teachers I spoke to said they couldn’t prove who did it, and I knew better than to tell my mother what was happening, so I walked around feeling the way I had as a kid—like an open target. It didn’t matter that I had some friends. Nothing made me feel safe. I assumed this was what life would always be like for me.

At the time, I had an obsessive crush on Josh, a boy in the ninth grade. Lots of girls had crushes on him, but mine was the most obvious because I followed him around and giggled whenever he spoke. One day, I noticed that people were staring at me more than they usually did as I walked between classes, and that the high-school girls laughed whenever I passed them. I grabbed a friend and demanded she tell me what was happening. “People are saying you gave Josh a blow job in the library,” she said quietly. I was more shocked than hurt by the rumor. I’d never even seen a penis in real life, and I didn’t want to. I’d given my summer boyfriend access to my whole body, and he’d used it happily, but even when I was naked, his jeans stayed on. Unlike the many others I’d endured, this rumor had traction, and by the end of the day, I was summoned to the principal’s office.

The principal and I were already enemies. British and in her sixties, she’d come to the school that year. She’d tried to be nice to me, but I refused to be nice back. I sat on her long floral couch as she pulled her chair out from behind her desk and sat down across from me.

Finally, she said, “I suppose you’ve heard the terrible rumor going around.”

I burst into tears. I was mad that I was crying in front of her, but it probably helped her believe me. “I didn’t do it!” I said.

She asked if I knew who started the rumor. I told her I figured it was the high-school girls who always made snide comments about my clothing.

When I was finally calm, she told me that she was going to call my mother. “Please don’t,” I begged. “It’s stupid. She doesn’t need to know.”

She told me she had to.

After school, I walked into the living room and threw down my backpack. When my mother spoke my name from the couch, I groaned. I dragged myself over and sat as far away from her as I could. “Your principal called.” When I didn’t speak, she continued. “She was so upset. She told me, ‘I can’t even say the word.’ ” She started to laugh, but caught herself.

I crammed my face into a pillow. “I didn’t do it.”

My mother nodded. There was nothing either of us could say that we hadn’t said before.

I didn’t understand how alone my mother was, or how she’d come to resent my father’s absence during this period until months later, when she mentioned that she’d once called him to vent about my behavior, though she didn’t say what I’d done to prompt the call. She was excited that she’d actually been able to reach him, but he’d interrupted her rant and said that he had tickets to a concert and didn’t want t

o be late. “He has a life there now,” she told me sadly. He’d created a world for himself that didn’t include her. She was solely responsible for dealing with me and all of my problems.

I understood the extent of the distance between them when I found a fax he sent her for Mother’s Day in 1993.

Hi! We don’t have any real contact with the U.S. calendar here so it was only this morning when several U.S. types got together that someone mentioned that yesterday may have been Mother’s Day. If that is the case, please accept deep and humble apologies for not having properly noted this important day!

Be it hereby duly noted and proclaimed that the finest, sexiest, and generally kinkiest mother in the world is one said Anita Kieras Yurchyshyn. A pillar of strength and inspiration to her daughters, an awesome source of love, support, and erotic dreams to her husband and a general source of liveliness and linguistic communications to the community.

We all respect her deeply and love her intensely. Happy Mother’s Day!

Love, George

When I read it, I was annoyed at my dad for forgetting a holiday that may have been important to her, but I couldn’t comprehend how hurt and invisible she may have felt.

Since I was still struggling with my schoolwork, my teachers and my therapist recommended I be evaluated yet again. The report, which is covered in my mother’s illegible notes, stated that I was there for issues with “spelling, behavior, fine motor difficulties, and peer relationships.” My school had told the doctors that I was

extremely hyperactive and impulsive, demanding of attention and sulking if deprived…explosive behaviorally, and appeared to have difficultly separating her personal preoccupations from class activities. Her teachers have hypothesized that attentional and emotional issues are combining to make it difficult for Anya to learn and function at age-appropriate levels.

The report stated that I had

mild to moderate levels of depression. She indicated she felt sad and discouraged about the future. She indicated she does not enjoy things the way she used to, expects to be punished, and has thoughts of self-harm but she would not carry them out.

After a day of tests, doctors determined that I had ADHD, and I was put on Ritalin. Because I often didn’t eat breakfast, the medication made me nervous. My schoolwork didn’t improve, but my behavior did because I was too anxious to interact with anyone.

My mother and sister visited my father in Ukraine for a few weeks that winter while I stayed with friends so I wouldn’t miss school. They returned with stories of empty supermarkets and department stores, and brown tap water. They’d seen churches, gone to the ballet, and visited artists in shared apartments or storefront galleries, but they hadn’t liked it. My mother said it was a terrible, depressing place and swore she’d never move there. I hadn’t known that was an option, and was glad that although it could be, it still wasn’t.

She returned to Ukraine a year later and took me with her. I was fourteen and had just dyed my hair black, and was living in overalls and men’s T-shirts. I had zero knowledge of or interest in the political and economic changes that were sweeping the region. The trip was a chore. I was annoyed to have to see my father and abandon my friends and free summer days for even a few weeks.

We arrived at the hotel where my father had lived for three years, having chosen, like most foreigners, a place that usually had heat and hot water, unlike even the nicest apartments in Kiev. The nodding staff said hello to my mother, then looked at me with shock before forcing smiles onto their faces. They said something to my father in Ukrainian. He laughed, said something to them, and then they all laughed together.

He saw me looking at him with suspicion. “They said they didn’t know that my daughter was a mechanic.”

“What did you say?” I asked.

“I said you’d be here for three weeks and could look at their cars anytime.”

I rolled my eyes and stomped to the elevator.

My father’s room was a suite. He used the large living room as his office. Towers of papers stood on his desk and on the brown carpet, and modern paintings, which he’d been collecting, leaned against the wall because he’d already hung the others he’d bought and there was no room left. He had a small TV and a VCR and three videos: Dick Tracy, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Madonna’s Truth or Dare. My father was a huge Madonna fan—he even bought her controversial book, Sex. When I asked why he liked her so much, he told me that she was a very smart businesswoman. I watched the videos at least a dozen times, and when I got bored, I watched American and European movies on one of the television’s few channels. All dialogue seemed to be dubbed by the same Ukrainian man, regardless of the age or gender of the person speaking the lines.

My mother and I trailed my father out of his room for meals in the hotel’s staid restaurant. Every time we sat down we were handed a menu, but after the first morning, we understood not to bother reading it. The waitress would tell my father the one or two dishes they were serving that day: usually boiled noodles and kashi for lunch; boiled noodles and kashi with an unidentifiable meat cutlet for dinner.

Kiev seemed overcast even when it was sunny. No one smiled. The roads outside the city were littered with cars. Some were wrecks that had been stripped. Some had been abandoned when the driver ran out of gas, and those, too, were missing tires, bumpers, even doors. We visited old wooden churches and spent a few nights in a resort that wasn’t yet open in the Carpathian Mountains, where there were only a few other guests. We went to Lviv, which I grudgingly agreed was interesting and pretty. Somehow I ended up hanging out with a group of local girls my age—perhaps they were distant cousins, or friends of some distant cousin—and we went to a decaying amusement park where I bought us all tickets and Popsicles, as I’d been instructed. My parents didn’t bother taking many pictures of me during the trip, and in the few they did, I’m scowling.

When other Westerners asked about my impressions of Ukraine, I’d say, “Ukraine’s awful!” I’d get them laughing with stories of choking on the random chunks of bone in a gray pork patty, or how once, when my father’s driver Igor was cut off on the road while he was taking my mother and me to a church, he sped up so he could cut off the other driver and forced him to stop. Igor grabbed a crowbar from underneath his seat and leaped out of the car as the other driver approached with a pipe. Igor forgot to put the car in park, so we started rolling backward and screaming until Igor abandoned the fight and ran after us. I couldn’t imagine why my father—why anyone—would choose to be there. Most of the Ukrainians I saw looked like they’d be thrilled if they could leave. But my father seemed happy. He looked like the people I saw on the street and spoke their language.

I was able to leave my school for a public high school when I reached ninth grade. My first semester, I received D’s in a number of classes and got suspended for skipping, but found there were a few things I cared about. I became a sex educator for a nonprofit, and began giving talks at schools and community groups, and also got very involved with my school’s drama program. I was as committed to ignoring my academic responsibilities as I was to ignoring any demand my mother made. I no longer asked to do things; I either told my mom I was doing them or just did them and dealt with the consequences, which were rare. She let me smoke pot and have my boyfriend in my room with the door closed. She’d never been strict, and I didn’t question why she’d become increasingly lax. Whenever she tried to corral my behavior, I lashed out like she was trying to leash me.

One morning, I encountered her while I was about to leave for school in a velvet blue crop top. I was surprised to see her; she still slept through the mornings like she had when I was a child.

She grabbed my shoulder. “You can’t wear that shirt to school. It’s barely a shirt! Go change.” Her voice was firm, but she was calm.

I told her that I wouldn’t.

She said that I would.

<

br /> I’d grown so accustomed to an absence of rules that being told what to do seemed like an outrageous injustice. I brought my face to hers and snarled, “Fuck you.”

Her smack was hard and fast, and the one I retaliated with equaled its force.

We glared at each other. I was appalled by my behavior, not hers. I mumbled “I’m sorry,” ran to my room to switch shirts, and stuffed the one I’d wanted to wear in my backpack so I could change into it at school. As I ran to the subway, I kept seeing my mother’s stunned face. She’d looked so tiny and vulnerable when I’d hit her. I knew I was responsible for the awful thing I’d done, but I tried to find a way to blame her for it.

When I came home late that afternoon, my mother was on the phone. She chased me down and handed it to me. I found myself listening to my father telling me how terrible I was for hitting her. Surprisingly, he wasn’t yelling; he was just trying to explain how wrong it was. I handed the phone back to my mother, then “ran away” to my friend’s house. Her mother, who knew mine, rolled her eyes when I told her not to tell my mother I was there. Later that evening, she found me and said, “Your mom says you can come home whenever you want tomorrow.” I understood this to mean that my mom wanted time away from me—not that I’d bullied her into giving me more space—and that made me feel even worse. I didn’t care that she’d hit me. I thought I deserved it. As angry as I was with her in that moment, and had been for years, I believed I’d made an unforgivable transgression. Smacking her felt worse than raising a knife to her. I hadn’t bothered regretting that. Seeing how sad and weak she’d looked when I’d hit her made me feel sorry for her.

When I came home the next day, both of us pretended the previous morning never happened. I was still sick about what I’d done, but I couldn’t make myself apologize again.

The following summer, we took a family vacation to Italy. My mother, sister, and I flew from America while my father flew from Ukraine. My parents had rented a villa in Tuscany with their old friends from England, Sue and Martin, whom I’d met in London a few times on family vacations and adored. My father was in a good mood. He never yelled, helped Sue with the cooking, and took long walks with Martin. But my mother’s energy was sour, and she picked fights with my father whenever she could.

My Dead Parents

My Dead Parents